In a world racing toward biodegradable everything, India has been quietly eating, praying, and composting its way through life for centuries—with no branding, no buzzwords, just a sense of innate balance. Nowhere is this more evident than in the humble containers that hold food in temples and on street corners: dried dona bowls made from sal leaves, rinsed coconut shells from temple offerings, banana leaves as plates, kulhads for chai. Compostable, yes. But also cultural. And somehow… holy.

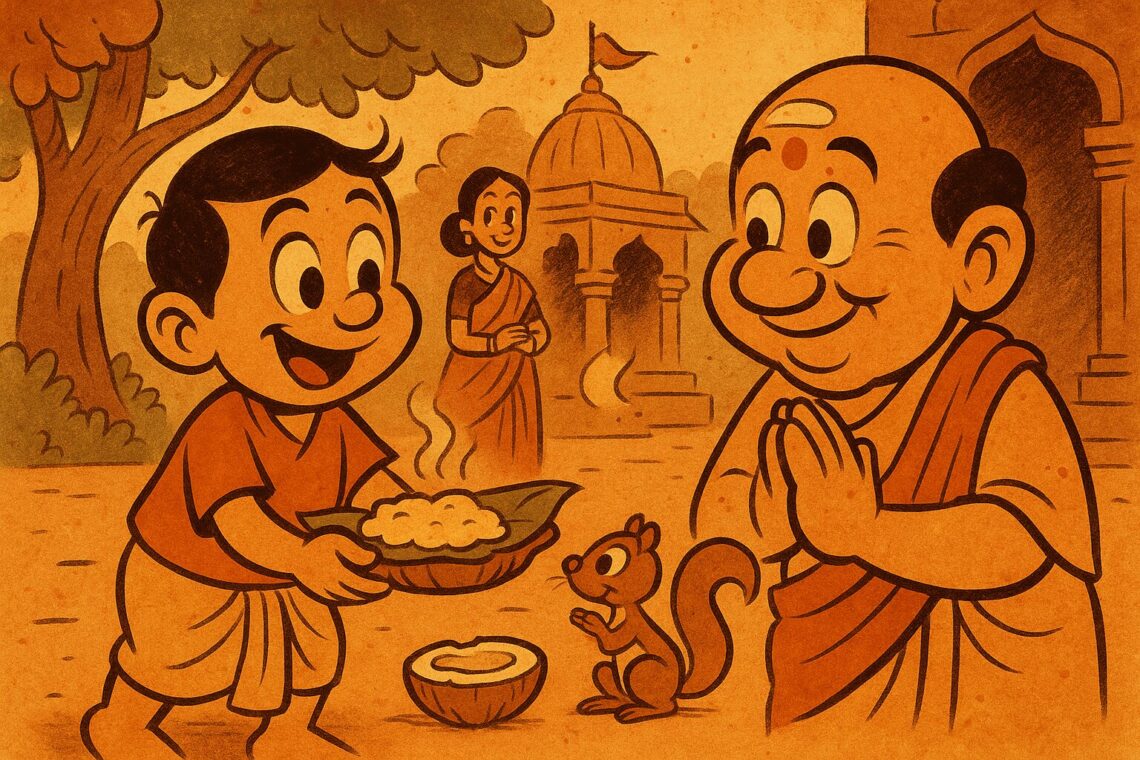

I first noticed it while standing outside a temple in Matunga. I’d just been handed prasad—a scoop of warm sheera spooned neatly into a leaf bowl. The edges were stitched together with thin sticks, and it nestled in my palm like it was grown just to serve this one spiritual purpose. There was no plastic. No need to “dispose responsibly.” When I finished, I simply tucked the bowl under a tree, where the crows would debate over sugar crystals and the earth would do the rest. That felt more graceful than any blue-bin ritual ever has.

The Leaf as a Plate

The banana leaf is possibly India’s most iconic edible canvas. Unfolded like origami and glistening with a wipe of water, it hosts wedding feasts, funeral meals, and everything in between. In the South, it’s not just a plate—it’s a rulebook. Curries go on the top half, dry vegetables on the bottom, rice in the middle, sweets in the corner, and chutneys on the periphery like spicy punctuation marks.

Eating on a leaf plate isn’t just about tradition—it’s about intention. The leaf forces you to eat mindfully, to clean up without scraps, to let flavors mingle without borders. And when you’re done? The plate folds up like a polite guest, leaving no waste, only aroma. Try that with styrofoam.

Temple Coconuts: Offering and Object

The coconut in temples is a multitasker. You offer it whole, break it with a thunk (or get someone more coordinated to do it for you), and then take the halved shell back with prasad nestled inside—jaggery, banana slices, a pinch of vibhuti. You eat it on the steps, the sweet juice soaking into the fibrous interior, and then place the empty shell beside the shrine or under a tree, where monkeys, squirrels, or time take care of the rest.

My grandmother used to say that even if you forgot to bring a bag, the coconut would never go to waste. It carried its own history and future. A vessel grown from the tree it eventually returns to. Circular economy, but with blessings baked in.

The Genius of the Kulhad

Then there’s the kulhad—a clay cup so humble, it feels almost wrong to call it genius. Found at railway stations and roadside tea stalls, it’s meant for one-time use, not out of laziness, but dignity. The chai absorbs the earthy fragrance of the cup. You drink it, you toss the cup, and it melts into the soil like a thank you note to the planet. No guilt. No carbon footprint. Just warmth in the hand and memory in the mouth.

Of course, the modern world tried to “optimize” the kulhad by replacing it with plastic. But something got lost in translation. The tea didn’t taste the same. The moment didn’t linger. And the guilt stuck around longer than the flavor did.

Street Food With a Conscience

In Delhi, you’ll find chaat served in dried leaf bowls that balance miraculously in one hand, while you juggle a steel spoon with the other. In Tamil Nadu, vendors fold newspaper into cones for roasted peanuts. In Bengal, puffed rice snacks come in hollowed-out sal leaves or stitched bowls. Even ice cream, in pre-scoop commercial eras, arrived in tiny kulhads or repurposed leaf cups. Lick, sip, toss, and the earth takes over.

This wasn’t environmentalism by design. It was by instinct. Before packaging became a verb, Indians used what grew around them. And when we were done, we returned it without ceremony—because not everything good needs marketing.

Global Goals, Local Habits

Today, when I see “100% biodegradable” printed in bold on expensive, almond-hued packaging in Austin stores, I smile. Because back home, our biodegradables didn’t have slogans. They had soul. The packaging was edible, or sacred, or just invisible. And while I appreciate innovation, I sometimes miss that leaf bowl of poha, eaten squatting on temple steps with no lid, no fork, no bin—just hands, intention, and gravity.

The Return to Simple Containers

Back in my kitchen, I’ve started saving coconut shells again. Not for ritual. For planting. I eat more meals on banana leaves—not because I’m nostalgic, but because the dishwasher is full and the compost bin needs a treat. And every time I do, I think of that dona bowl from Matunga. Simple. Sacred. Unbranded. Just enough.

Born in Mumbai, now stir-frying feelings in Texas. Writes about food, memory, and the messy magic in between — mostly to stay hungry, sometimes just to stay sane.