There’s a kind of silence that only exists under a full moon. Not the sleepy kind, not the eerie kind—something softer. Expectant. Like the night is holding its breath. And on those nights, in our house, there was always one thing on the stove: kheer. Simmering slowly, milk thickening into memory, rice softening like prayer, sugar just enough to coax a smile. This wasn’t dessert. This was offering. Because on certain nights, my grandmother said, “The Moon God comes hungry.”

I never questioned it. Didn’t ask for a source or a scripture. It was one of those things woven into the air of childhood—the same way you just know to touch namaste when you pass a temple or how new clothes must smell of incense before they’re truly yours. When the moon was full and round, we made kheer. Because tradition said so. Because someone long ago believed it. Because it felt good.

The Ritual of Sweetness

Kheer isn’t a flashy dish. It doesn’t demand technique or garnish. It demands time. A slow stir. A watchful eye. A quiet presence. You start with milk, whole if possible, because richness matters. Then rice—washed, soaked, patient. Sugar comes later. Cardamom, even later. And sometimes raisins and cashews if someone remembered to roast them. But even without them, it’s enough. It’s always enough.

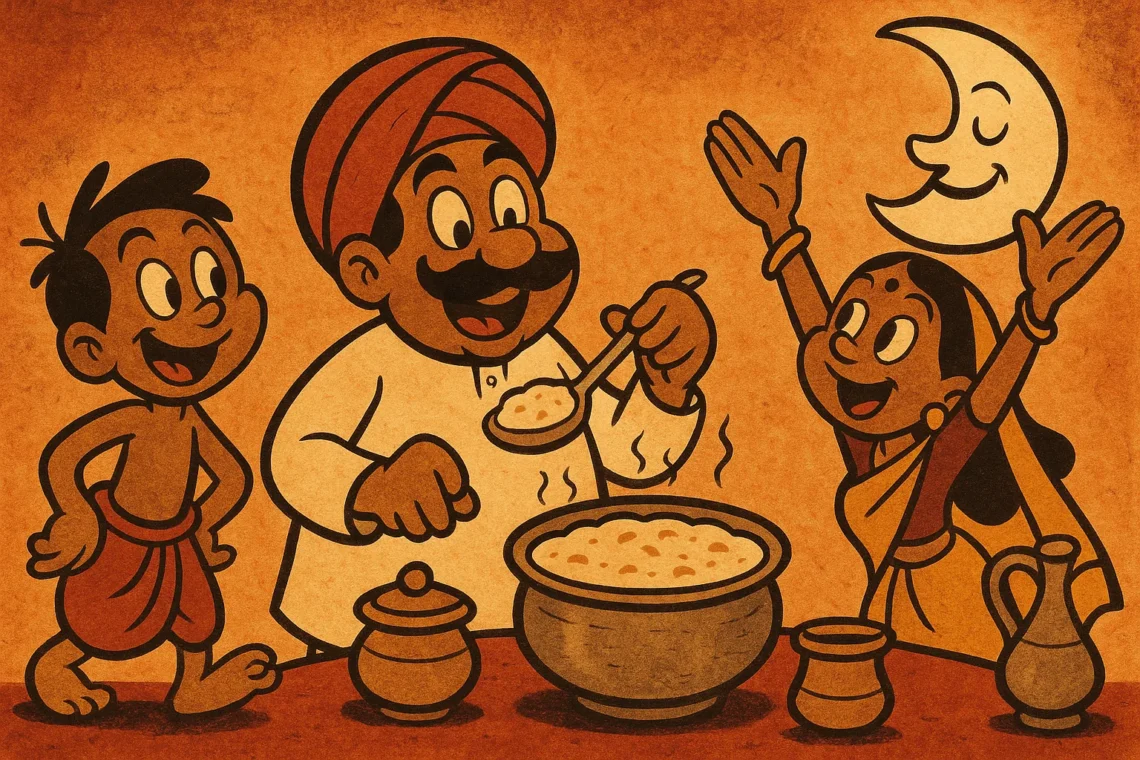

My grandmother used to place a small steel bowl of kheer on the windowsill. Just a little. “For Chanda Dev,” she’d say, as if that explained everything. “He watches us, feeds the tides, blesses the harvest. He doesn’t ask for much—just some sweetness.” And then she’d turn back and scoop out the rest into bowls for everyone else. But I always believed the first one tasted different. As if the moonlight had cooled it, added something extra.

Myths on a Stove

Years later, I learned that kheer for the moon isn’t just our family thing. It lives in Karva Chauth. In Kojagiri. In Sharad Purnima. Across regions, languages, and recipes, people look up at the same moon and stir milk the same way. Some add poha, some use sago, some even add condensed milk (yes, modern gods don’t mind shortcuts). But the essence is the same: on this night, we offer sweetness. To the moon. To the sky. To ourselves.

There’s something soothing about it—this idea that we cook for the cosmos. That our kitchens aren’t just places of need, but of gesture. That a humble bowl of kheer can cross thresholds and speak to gods. That even if no one else is watching, the moon is. And he likes his dessert slow-cooked.

In My Apartment Kitchen

Now, in Austin, I do the same. Maybe not every month, maybe not with the same steel bowl, but sometimes—when the night is still and the milk in the fridge is about to expire—I stir. And the apartment smells like cardamom and childhood. I text my mom. “Kheer banayi aaj.” She replies, “Chanda khush hoga.”

I eat it warm. Sometimes cold, if there’s any left the next day. But the first spoon always tastes like home. Not just the physical one. The emotional one. The one where food wasn’t just for the body. It was for the atmosphere. For whatever needed healing, blessing, comforting. Even if it was just a quiet moon, doing its job without applause.

Because kheer isn’t just milk and rice. It’s lullaby. It’s devotion. It’s our way of saying, “We see you too.” And if the Moon God really does come hungry—well, we’ll be ready.

Born in Mumbai, now stir-frying feelings in Texas. Writes about food, memory, and the messy magic in between — mostly to stay hungry, sometimes just to stay sane.