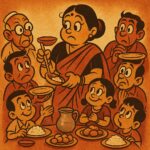

There was a jar in my grandmother’s kitchen that sat like a throne on the highest shelf. Wide-mouthed, glass-bodied, and always catching the afternoon light, it wasn’t particularly fancy. No intricate patterns, no fancy latch, just an old jam label that had faded into invisibility. But if you grew up in a joint family in India, you know: the more ordinary the vessel, the more sacred the contents. And this one? This was the forbidden jar.

We were told, in no uncertain terms, not to touch it. No stool-climbing, no sneaky attempts when elders were napping, no “I was just cleaning the shelf” excuses. It was a universal law in that house. The Geneva Convention of grandkidhood. You broke it, you got The Look from Daadi—a look that said you’d not just disrespected her kitchen, but possibly shamed your ancestors.

Preserved in Spice and Suspense

The jar changed seasonally. Sometimes it held raw mango pickle—cut into uneven cubes, soaking in mustard oil with flecks of kalonji and fennel seeds. In winter, it might be full of gud-til laddoos or methi-dana soaked in lemon juice. But mostly, it carried achaar. Not the store-bought kind, but the one made in sun-drenched batches, left out on the terrace under thin muslin cloths, and stirred with wooden spoons longer than your forearm. Each jar had a fermentation cycle longer than some of our summer holidays.

But that’s not why we weren’t allowed to touch it. The restriction wasn’t about the food. It was about the sanctity of memory.

The Pickle as Time Capsule

Daadi made pickles like she was bottling up a mood. The mango pickle from the year my uncle got married was different from the one when my cousin broke his leg. She never wrote dates on the jar; she remembered through flavor. “Oh, this one’s from the year of the floods,” she’d say while fishing out a piece, her fingers glistening with oil and experience. “This one turned out extra spicy because your bua was in a bad mood when we were making it.”

We weren’t allowed to touch the jar because it wasn’t just a container. It was an archive. A memory bank. A journal entry in cumin and asafoetida. We kids didn’t understand that then. All we saw was a jar filled with temptation and a rule that made no sense.

The Day the Jar Broke

It happened during a monsoon storm. A shelf collapsed. Among the spices and lentils and rattling tins, that glass jar fell. We stood there, barefoot on cool kitchen tiles, watching oil seep into the floor like it had a mind of its own. Daadi didn’t shout. She didn’t weep. She just bent down, picked up the biggest shard, and said, “It was time.”

I remember helping her clean it up. She didn’t try to save the pieces, didn’t salvage the remnants. Instead, she told me stories about that batch—how the mangoes had been too ripe, how the salt had clumped, how the lid never quite shut right. And just like that, the jar went from sacred to story. And that, in hindsight, was its true power all along.

The Shelf Without a Guardian

Years later, when I moved to Austin and set up my own apartment, I bought a jar. It wasn’t special. Just something from a home goods store. I filled it with lemon pickle sent by my mother, and instinctively placed it on the top shelf. I don’t tell guests not to touch it, but no one ever does. It sits there like a little lighthouse of memory, glowing faintly through the kitchen sunlight. Sometimes I open it just to smell the past. A kind of edible nostalgia.

I think about that forbidden jar often. About how food was never just food in our homes. It was a way of holding onto people, of freezing time, of encoding emotions in mustard oil and sunlight. The jar we weren’t allowed to touch wasn’t off-limits because we were children. It was because we hadn’t yet earned the stories it held.

And now, with every jar I fill, I try to write my own version of those stories—one spoon at a time.

Born in Mumbai, now stir-frying feelings in Texas. Writes about food, memory, and the messy magic in between — mostly to stay hungry, sometimes just to stay sane.