Growing up in Mumbai, Sunday lunches at our extended family home followed a choreography so tight it could rival a temple procession. Grandmothers cooked, uncles laid out mats, children were made to sit cross-legged in rank order, and food was served with clockwork efficiency—always from right to left, always starting with the eldest, and always by the same people.

I never questioned who served the food. It just happened. My mother did it when we had guests. My aunt took over when the setting was more formal. My cousins and I were assigned second servings once the rice rounds began. The men? They usually sat, discussed cricket, and waited. It wasn’t until much later—years into adulthood and a few thousand miles away in Austin—that I began to notice the quiet rules behind who gets to serve, and why.

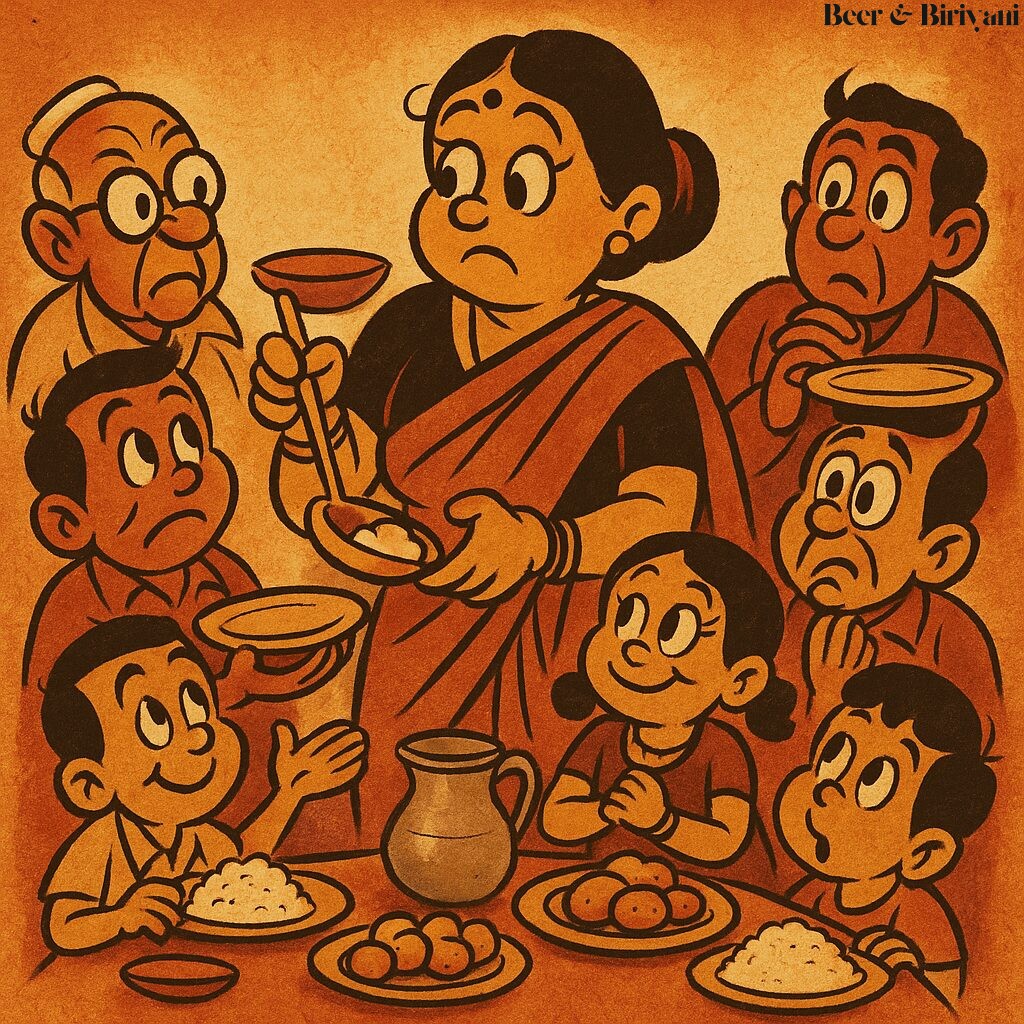

Serving Is Never Just About Food

In most Indian households, serving food isn’t a casual task. It’s laced with signals. Who serves whom, how, and when reveals a hidden hierarchy. It’s often gendered—women serve, men eat. Sometimes it’s based on age—elders serve juniors as a sign of care, or juniors serve elders as a mark of respect. Sometimes it’s about caste, though no one ever says it out loud. But you notice who is allowed in the kitchen. Who is asked to sit. Who is subtly guided to “help with plates” instead of “join the meal.”

These aren’t rules you read. They’re absorbed—like steam into hot rice. And once you begin noticing them, it’s hard to unsee.

Temples and the Caste Line

I remember visiting a temple in Udupi as a teenager, where I ate on a banana leaf seated in a long hall. Volunteers glided past, ladling sambar and rasam with military precision. Later, I learned that only certain members of the temple committee—mostly upper-caste men—were allowed to serve the food. Others could assist, but the act of ladling onto a leaf was a privilege.

In some temples, especially in South India, there’s a long and complex history of who can serve prasadam. The Dalai system in Karnataka, for example, designated specific castes to serve specific foods. These rules weren’t always challenged—they were inherited. And though many institutions are evolving, the ghosts of those systems still linger in small acts: who enters the kitchen, who touches the vessels, who stands behind the ladle.

Weddings and Silent Hierarchies

At Indian weddings, especially those with sit-down meals, the act of serving becomes an almost ceremonial display of hospitality. You’ll notice the difference between who carries the food and who actually scoops it onto the plate. Younger men might ferry the buckets, but it’s often a senior family member—preferably male—who ladles the first helping of dal. Why? Because it’s not just about giving food. It’s about offering status, hosting pride, and, sometimes, claiming a position within the social pecking order.

And if you’re on the receiving end, your place in the line often reflects your perceived importance. VIP guests get served earlier, or receive extra ghee without asking. Everyone else watches and adjusts. It’s not formal, but it’s noticed.

The Gender of Generosity

At home, though, the division is clearer. Women serve. Women feed. And in many households, they eat last. My mother always claimed it was practical. “If we sit down, who will get the second helpings?” But now I wonder how much of that practicality was training. Even when there was help, she preferred to serve. It gave her control, yes, but also identity. Her hospitality was her power. And yet, it was rarely recognized that way.

It’s not that men don’t serve. But when they do, it’s often seen as exceptional. Praiseworthy. Instagrammable. “Look, Papa’s serving dinner tonight!” As if the act is cute rather than collaborative. Serving becomes a novelty, not a norm.

Who Gets to Serve in My Home Now?

In Austin, things are fuzzier. My wife and I take turns. My son is slowly learning to serve himself. But I catch myself slipping into inherited patterns—offering to serve our guests while she quietly clears their plates. Sometimes I remember to switch roles. Sometimes I don’t.

I now try to notice more. Who’s standing at the buffet and who’s seated. Who’s watching the food disappear while pretending not to be hungry. Who is performing generosity, and who is quietly expected to embody it.

Small Acts, Big Meanings

Serving food in India has always been an act of care. But also, of control. Of offering and of authority. In every spoonful, there’s a silent message: where you stand, what you’re owed, who gets to give, and who must wait to be given to. These messages aren’t always harmful—but they aren’t always harmless either. They’re just… there. Simmering under the curry. Folded into the chapati. Tucked between courses.

And maybe that’s the point. Food tells stories. But how it’s served? That’s where the real story begins.

Born in Mumbai, now stir-frying feelings in Texas. Writes about food, memory, and the messy magic in between — mostly to stay hungry, sometimes just to stay sane.