I still remember the taste of that first spoonful of ven pongal handed to me outside the Kapaleeshwarar temple in Chennai. It was hot, slightly sticky, and clumped in a way no food scientist would approve of. But it tasted… holy. Not in a metaphorical way. Holy in the literal, this-has-been-offered-to-a-god-and-come-back-changed kind of way. I was eight years old, and that pongal set a standard that hotel buffets and homemade efforts have been trying—and failing—to meet ever since.

Why does food taste different when it’s served from a steel bucket by a temple priest onto your cupped palms or a banana leaf? Why does that watery sweet pongal or spiced chakkara pongali or two-spoon dollop of tirupati laddu carry so much weight? Is it just nostalgia? Is it the hunger? Or is something else at play—something simmering beneath the turmeric and ghee?

What Is Prasadam, Really?

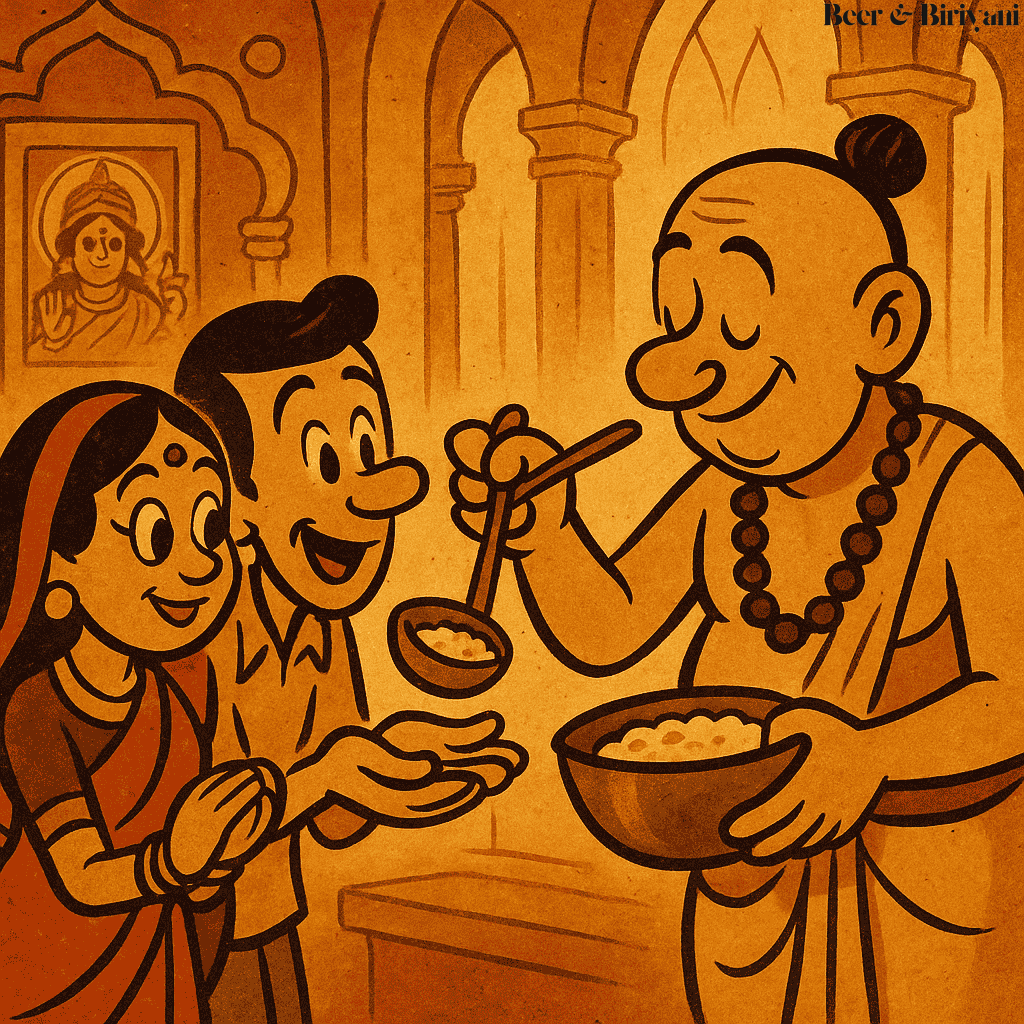

In Indian tradition, bhog is the food prepared and offered to the deity. Prasadam is what returns from the divine—blessed, transformed, no longer just food but a form of grace. Across regions, the names shift. In the south, it’s naivedyam. In the east, bhog. In ISKCON temples, it’s all prasadam from the get-go. But the central idea remains: when you offer food with devotion, it returns infused with something more.

And I know, that “something more” sounds vague. But when you taste temple prasadam—whether it’s Jagannath Puri’s chhapan bhog, Kanchipuram’s puliyodarai, or the simple banana and sugar handed out after a morning aarti—it hits different. Not fancier. Not more gourmet. Just… deeper.

The Alchemy of Offerings

Part of it is the process. Temple food is made differently. It’s cooked with intention, often in silence, sometimes by Brahmin priests or temple cooks who’ve trained in one recipe their whole lives. In Jagannath temple, for example, food is cooked in earthen pots stacked over firewood, in a very specific order. No tasting is allowed. It’s not cooking for consumption—it’s cooking as offering. That mindset changes the food. Or maybe, it changes the person eating it.

When my aunt made panakam (a jaggery-lemon-cardamom drink) at home during Rama Navami, she insisted we place it at the puja altar first. Only after the bell rang and the incense smoke cleared could we take a sip. And you know what? It always tasted better post-offering. Coincidence? Maybe. Or maybe reverence is an underappreciated seasoning.

It’s Not Just the Taste

There’s also the environment. You’ve stood in line for an hour. You’re sweaty, a little sunburnt, mildly overwhelmed by the sound of temple bells, Sanskrit chants, and the low murmur of collective devotion. And then, someone places something warm and sweet in your hands. No cutlery. No frills. Just a simple transfer of energy—from the divine to the kitchen, to your hands, to your heart. That moment is edible.

I’ve had kesari that was too sweet at home, but divine in a temple. I’ve rolled my eyes at dry coconut burfi at weddings, but savored every grain of it when it came from a puja thali. It’s not logic. It’s context. And maybe just a little bit of surrender.

Why You Can’t Replicate It at Home

Of course, I’ve tried. On Ganesh Chaturthi, I go full tilt: modaks steamed, coconut grated, ghee added with the seriousness of a monk. But no matter how precise I am, the first batch never tastes like the ones from the Ganpati pandal. My son once said, “Yours are good, but the other ones feel more… temple-y.” I didn’t argue. He was right.

Because what’s missing isn’t an ingredient. It’s the collective energy. It’s the singing in the background. The smell of incense blending with jaggery. The dozens of aunties standing shoulder to shoulder, whispering mantras while stirring paal payasam. That’s the flavor you can’t package or freeze.

Food as Offering, Not Ownership

Temple prasadam reminds us of something profound: that food doesn’t have to be about control. It can be about letting go. You offer it. You receive it. You don’t critique it, modify it, or plate it with microgreens. You just accept it. As is. And maybe that’s the true recipe: reverence, simplicity, and timing. Especially timing—prasadam always comes when you need it most.

So the next time someone hands you a tiny piece of coconut, a tulsi leaf, or a spoonful of sweet rice from a puja plate—pause. Close your eyes. Let it melt. Taste the quiet.

Because sometimes, food isn’t about feeding the body. It’s about feeding the space between the heart and the sky.

Born in Mumbai, now stir-frying feelings in Texas. Writes about food, memory, and the messy magic in between — mostly to stay hungry, sometimes just to stay sane.