There’s a jar in my mother’s kitchen that sits untouched for 358 days a year. Round, dented at the edges, painted in colors that have long faded to a polite blush—it lives on the top shelf like a seasonal deity. And once a year, just before Diwali, it descends. Not with ceremony. Just purpose. Because this jar holds only one thing: Diwali sweets. And nothing else ever.

You don’t mess with this jar. You don’t borrow it for dry fruits in June. You don’t use it to store leftovers. You don’t question its hibernation. You just know—when it appears, something sweet and celebratory is on its way. It’s not just storage. It’s tradition, in cylindrical form.

The Tin with a Timetable

My grandfather once brought this tin home from an old sweet shop near Crawford Market. The sweets are long gone, the shop is now a saree boutique, but the tin remains. Originally gold with a red rim, it now has a faint metallic shrug of color. But come Diwali, it still smells of sugar and ghee and a little bit of deep time.

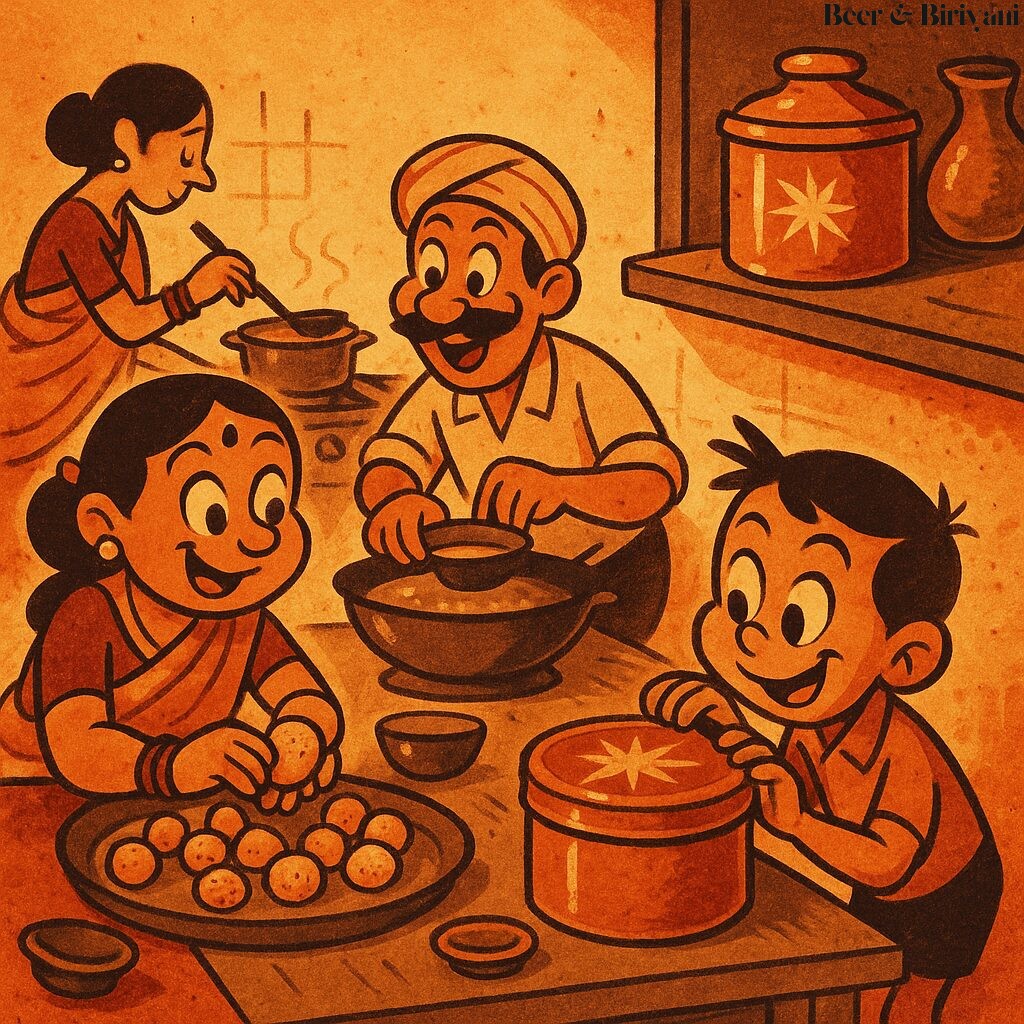

In it goes the karanji, the laddoos, the chakli (in defiance of categories), and sometimes a renegade square of barfi that never stays for long. Everything gets nestled in wax paper or an old napkin. And even though we now have airtight, food-grade, click-lock containers that promise freshness till the next financial year, this tin is the one we return to. Because this one has rules. Memory. And the unmistakable aura of once-a-year sweetness.

Why Only for Diwali?

I once asked my mother why we didn’t use the tin the rest of the year. “Because it’s not right,” she said. Which, in Indian family logic, is a full explanation. There’s no spreadsheet, no origin story. Just a feeling. The tin is tied to a season. Its emptiness is part of its purpose. To use it in April for storing poha would be like putting fairy lights up for a dentist appointment. Functional? Maybe. But deeply unsettling.

It’s not about efficiency. It’s about rhythm. That one object waiting all year to fulfill its only job. And doing it well. Like a character actor who enters just for the third act and steals the show.

Sweets and the Contract of Joy

The Diwali tin isn’t just a container. It’s a contract. It promises that sweets will be made. That someone in the house—your mother, your aunt, your neighbor who makes shankarpali better than any bakery—will bring something over. That there will be frying, and ghee, and a moment where someone says, “Don’t eat it now, it’s for guests,” while you steal a piece anyway.

The tin is also where leftovers live after the festival. The slightly cracked mysore pak. The broken edges of anarse. The laddoos that went a little soft. Each piece a memory of a week that smelled of cardamom and sounded like firecrackers. You eat them slowly, like rationed nostalgia. Until one day, the tin is empty again. And it goes back to its corner, waiting, patient, noble in its uselessness for another year.

The Tin in Diaspora

In Austin, I now have a tin of my own. It’s not vintage. It’s not dented with stories. It came from a chain store and was meant for cookies, but I’ve claimed it. I use it only in November. I line it with parchment. I fill it with besan laddoos I’ve learned to make (almost like my mother’s), and once with a desperate batch of microwave karanji that I’ve sworn never to speak of again.

And yes, I don’t touch it the rest of the year. Not because I’m superstitious, but because I now understand. There’s something sacred in seasonal containers. Something calming in rituals that repeat. In jars that only open when joy is expected. In the quiet, firm rules of a family kitchen where some things are used only when the world feels festive and glowing.

More Than a Jar

These tins and jars and boxes are like little time machines. They don’t just hold sweets. They hold the build-up, the anticipation, the sigh of a guest who says “Oh good, shakkarpare!” without knowing how much ghee went into making it. They hold a mother’s tired but proud face, a grandmother’s recipe written in oil stains and guesswork, and a child’s sticky fingers reaching in, again, despite the warning.

And so, when I see that jar each year, I smile. Not just for the sweets it carries. But for the sweetness it expects. The quiet message it sends: It’s Diwali. Make something. Share something. And let this tin do its job, just once more.

Born in Mumbai, now stir-frying feelings in Texas. Writes about food, memory, and the messy magic in between — mostly to stay hungry, sometimes just to stay sane.